- Home

- Annie Liontas

Let Me Explain You Page 2

Let Me Explain You Read online

Page 2

If the wife had continued to make herself up like this, he would not have gone looking for Rhonda. If the wife had looked less fat and more fatty, like steak, like ribs melting into honey, he would not be here; if she had just shut up sometimes and talked to him. He, himself, was getting fat, OK, but not too fat for a man of over fifty. The lines in his face like slits where you deposit pity. His eyes and his skin worn, maybe from smoking but more from stress, like maybe God had been rubbing an elbow over him too long. His hair, thinning and gray, like all of his brothers, some of whom were dead. His mustache, it was still impressive because it was not American, it was as Greek as democracy, it was the thing Rhonda first liked about him, but it was also graying. Now it is the tail of a powerful black ox, when once it was the tail of two powerful oxes! Yes, he was becoming old but, look, he could get a young business-professional mistress!

OK, not mistress, because he was nothing with his wife these days, but mistress because what he had with Rhonda still felt like something he had to keep from people.

Rhonda didn’t look up until he slid a Styrofoam package onto the desk. “I come to bear gifts,” he said. He meant sandwich, which he had not eaten in his rush to get to Starbucks.

“I ate, malaka. It’s four o’clock.”

“I know you. You’re hungry.”

He stared down at her, waiting to be invited closer. He placed the yellow flowers with the red centers where she could see them. Soon enough she turned her knees. That made him feel good, that he could get her to turn like that. He came around the corner of her L-desk and sat on some papers. He watched her navigating a computer older than his own. He knew she was secretary to somebody, but the way she conducted business, it was as if she were the one to be answered to.

“I don’t know how long you expect me to live on Styrofoam for,” she said.

The wrinkles in her skirt were deep, which meant she had been working all day. He liked that about Rhonda, that she worked as hard as he did, because if you worked hard it meant you loved hard. Carol only worked hard when her job replaced her husband; Carol had no love for him. Rhonda’s problem was that she did not get enough love. She was tired of waiting. She did not want to live with her sister anymore just because some loser left her and their children behind. What she wanted was a big house together, what she wanted was a future for her sons. But the last thing he could give her, at fifty-three, was a marriage and a father. It smashed his heart, but she was not a wife he could take on his arm and walk through town, and the problem was she knew that now.

He pulled out the sandwich, which was soggy at one end. He tore it off for her, took a napkin out of his pocket.

“I deserve cloth napkins. And waiters. And wine.”

He put the sandwich down and rested his short, strong hands on her shoulders. He knew what she wanted: to go out. Always, they spent time alone—here, at his apartment, at her sister’s house when her sons were at a sleepover. Or else, with strangers, on planes or boats or in hotels. He covered himself with the half-truth that he was still getting used to being on his own. The other truth was that this was new for him, being with such a dark woman. Every time he brought his face to hers, he was surprised by how brown she was. The people he knew, they would see them together, and they would call him the soft white bread of the roast beef special. And was that any way to be seen? For any of them?

She was showing him how good she was at multitasking—typing and ignoring, waiting for the talking parts that would be useful to her. She was pushing her big knees up to the desk.

“What do you want?” he whispered, his mouth speaking into the gold earrings he had purchased. “Do you want another cruise? I can cruise you.”

This was not a real offer, of course, but at one time it would have been. In the last year, he had spent much money on her: $10/month for the interracial dating site where they met. $300 here for a necklace, $300 there for shoes and clothes, $400 so she could fly down to her family reunion in Atlanta, $500 to fix her car. How much hundreds on meals together, how much monies for the twins, Henry and Miles, to play Little Leagues and Boy Scout. He didn’t mind, because he had always wanted sons, he had always wanted to seem kind to children. He had wanted to like Henry and Miles; he had wanted Henry and Miles to like him. He was a good inspirational man to look up to, for two twin boys. And Rhonda returned what she cost, just like a woman, just like a partner should, not like his wife had been. He would never admit it, he knew it was not the way to think of someone you cared about, but he couldn’t help himself: it was a way to see her as his equal. She was proud to be with a smart, successful Greek man, just like he was excited—so excited, he sometimes felt reduced to jiggling, jangling change—to be with a smart, achieving black woman.

He liked wooing her, liked realizing that even when he did not choose big women, he chose big women. Their fourth date, he felt all of her weight on him, letting him know just how gravity worked, reminding him that this way of being pressed down was another way of being held. What he felt with Carol, in the beginning, until it just felt like being pressed down.

He was still kneading Rhonda’s shoulders, hoping this squeezy would lead to other squeezy. He was only a man. They had not seen each other in many days; this could be the last time, of his life, that he has sex. He did not like the idea of his organ softening in moist soil, and he was desperate that she should bring it to life. She should treat it like a waterless plant that is arching its stem toward moisture. Thinking about a coffin, which to his mind looked like a wooden crate for produce, and seeing himself lying naked in it, his dandelion losing color and shape after being left in the cold—it made him want everything at once: to be held, to penetrate her, to sob, to feel life dripping out of him, to feel life dripping into him, to climax and die, to confess the dream, to let her in and shut her out.

Rhonda pulled away to reach into the filing cabinet. She said, “You don’t want a cruise. You want something cheaper than that.” After two weeks, she was still mad with him.

He had taken her to Philadelphia—because all the people who would recognize him were in New Jersey, except for his daughter who was workaholic like him and, no question, at her restaurant—when they ran into someone he knew. It was in the old, cobbled streets of the city, on a road that had purported to be deserted. They were coming out of a cigar shop and the businessman was going in. Rhonda was standing so close to Stavros he could not get away. He could smell her fruity breath and felt the fabric of her coat brushing against his waist. “We work too hard,” Stavros told the businessman. “A man should have fun sometimes.” As if Rhonda were fun, takeout. As if she were not the woman of his life.

The man, a regular at the diner, gave a chuckle. “I hear you,” he said. Then he looked at Rhonda as if she were leftovers, and Stavros did nothing about it.

Rhonda watched the man leave, then she stepped onto the curb. Stavros, still in the street, was made to look up even higher at her and at the power lines swooping above. “You’re about to work a lot harder,” she said. She took a cab, would not return his calls.

The businessman idiot, he couldn’t keep his mouth to himself.

Stavros was lonely, he missed her; she had a way of walking with him through the world that made him feel as if he had just gotten here; she made him feel like a child, and she was going to teach him how to hold a fork and look at trees. It should have been enough to beg her to come back. But Stavros was not familiar with begging. The businessman, he returned to the diner. Everything between them was the same except for one small order of business. He had always paid his checks, even if it was a sandwich, with fifties; now he had a funny way of paying with only small bills. This is how Stavros knew it was over with Rhonda. Even this late in his life, Death coming, he could not bring himself to be with such a woman. He could not walk with her on his arm or have her at his funeral.

Did that mean he was coward? No. Maybe. No.

He was a man who did not know how to be any other way in the world,

even at the end.

Rhonda rolled her chair back. “You know I don’t keep my boys waiting.”

He had forgotten all about Henry and Miles and baseball practices. “Give them until five.”

Rhonda was sliding a binder into a bag. She was putting on her blazer. “You mean give you until five.”

Stavros helped her into the jacket with the intention of helping her get it back off. “Not me. Us.” He ran his hands up her sides. The produce crate came to him. He buried his mouth into her neck, where it smelled like Sunday. She adjusted her jacket, her message that he was not going to get any squeezy squeezy.

She stopped at the door with her keys ready and he realized that what she was actually telling him was goodbye. He had seen this many times at the diner, some woman looking across the table, telling the man that their relationship was dead; he had faced it himself, of course—twice. But with Rhonda, it felt different. She took her time, never shy with her eyes. This look was the look she might leave on his grave. Yes, she loved him. No, even now he could not return that look. He could not say, Let me give you my remainings of the day.

He said, “Take to them the chicken sandwich, at least.” He put it back in its container, happy it was cut in half, one equal part for each boy.

She would not let him walk her out, made him leave while she locked up. He watched her from his car. He smoked, she flipped down the mirror for lipstick. He watched her smooth her hair. She always looked nice for her sons. He hoped God was not too busy to see what a lovely woman she was. The one thing he had always known about her: she never needed him. In that way, she was superior to him.

He thought back to the first time they met, an expensive restaurant an hour away, in Delaware. He got there early, she got there on time. He stood when she arrived, kissed her cheek. That night she was in a skirt, too, and a shirt cut low, which made him order a bottle. Only, he did not like her name, which to him sounded like a man’s. He could not make an easy, pretty nickname of it.

“You like merlot?” he asked, waving the waiter over.

“I like it all,” she said.

He felt giddy when the waiter filled their glasses. He did not look up at the man, partly to show that he was more society and partly because he did not want to see what the man thought about these two people, one white and one black, on a first date off the internet. She sipped the wine without bringing it up to her nose. He showed her how it was done. “I know about wine,” he said, “because I am from the country where all of the songs are about wine.”

She asked him where that was. “Your accent,” she said, “it’s very strong. I like that.”

He told her about Greece and enjoyed how her eyes lit up at the emerald-blue water, the islands carved out of marble, the summer lovers, landscapes as early as breakfast and long as sunbathing. Introducing her to this paradise, he felt as if he had been the one to make it. “I will take you one day,” he told her. “I can show you everything.” Oh, he meant it. Wanted to. He could be one of the Richie Riches and spend money on one good time for them both.

She laughed with her mouth open, like a Greek. He was surprised by her teeth, the space between them, the way he felt he could fit his whole body inside, and how it had made him want her even as it made him nervous, cautious. His wife did not have space between her teeth for him. His wife, even when they first met, when they pressed against each other inside two beers and a crowd, did not make him feel swallowed whole the way Rhonda did. Rhonda talked a lot. She told him about her dream to be a travel agent and her night classes and her nine-year-old sons. She told him she had no time for small men.

“It’s all over your eyes. I saw it the minute I came in.” She laughed. “Don’t be afraid of the bigness, Steve. Sometimes, bigness brings joy.”

But a man like Stavros Stavros Mavrakis cannot have joy for very long. His entire life has been leading him toward the end of things. He has and has not written his end into being. His decision on the email letter to his family, it only points at the sun through the clouds. He sees the sun but cannot make it stay through the night, any night, no matter how he tries.

He is not planning his death—that is not the right way to explain it. He is Sweeping Away the Hay and Cockroaches from the Floor of Destiny. He is Thawing the Meat of What Is To Be. He is aware of death the way you might try to become aware of the wolf in the forest, only to understand that the wolf has long been aware of you. He is not sure that God will meet him halfway or any way. So far, it is clear that you take maybe one, two steps with someone, and then you make the rest of the journey alone; it could be that Stavros will make it to heaven to find out that he is the only one there. But would that be so different from this crowded life, where you were left to yourself?

This was it, the final nail in the crate.

Rhonda’s car pulled out of the parking lot. Stavros watched until it became confused with all of the other cars. Since his arrival to this country—this state—over thirty years ago, he has never gotten over how many cars can be on one road and how, in those cars, day after day, most people are driving with no one beside them. This, plus the sun quickly moving away from him, reminded Stavros that he would spend tonight alone. Then he thought of the goat.

He parked in the back of the diner, as usual. No one came outside. The goat sat on its curled haunches, as if it were a cat.

“I am home,” he said.

The goat did not flinch. It accepted a Saratoga with its long tongue.

“Do you know the evil three, goat? θάλασσα καὶ πῦρ καὶ γυνή Sea and fire and women.”

The goat raised its head.

“Good you only have to worry about number one or two.” He squatted in the darkness some feet away. He smoked. “These women, goat, they are killing me to death.”

The goat settled down again. This one sympathy was exactly what Stavros needed.

Dusk began to mask their surroundings. It made Stavros feel as if he were in another time—first his childhood, the village, and then, staring at the goat, its head more formation than skull, he could have been a shepherd in another lifetime, isolated on a mountain with his flock and a purse of dried meat, a knife, a flute.

Stavros was quiet. He felt satisfied, for a few moments, that there was no one to talk to.

If We are who We are supposed to be on the outside, We are who

We are supposed to be on the inside.

CHAPTER 3

* * *

Stavroula answered her father’s email: with love.

And food, of course.

In the cramped white office, Mr. Asbury sat. Out of respect, she stood. She could hear blades, searing from the kitchen, the sous yelling about cross-contamination. He was fastidious, which she liked. Under it all, the vacant hum of the nearby ice machine. The middle of a dinner rush on a Saturday, and she had insisted that they talk now. No, it couldn’t wait. Her new seasonal menu—her answer to her father—was going out tomorrow. It was printed on cream-colored paper in an embossed font that you expected to taste like crème brûlée.

Mr. Asbury mouthed consonants as he read, his thin legs hooked around a stool. He was all brow and snowy arm hair. His eyes were fin-blue, like his daughter July’s, his skin pink. He was a father first, and a businessman second. Never a dictator. Nothing like her own father. Mr. Asbury would have never sent an email like the one she received, but Mr. Asbury also would not have made a good cook, having none of her or her father’s bullheadedness and intuition. Mr. Asbury was a wonderful boss. He respected Stavroula, acknowledged her as a person and an artist and a partner. He trusted her to do right by Salt. He had recruited her for his restaurant two years ago. Stavroula had not yet made up her mind about how long to stay—she had a history of moving from one kitchen to the next—but there were things keeping her here. Such as, she had exclusive creative control of her kitchen. Reading the menu, Mr. Asbury knew that.

Like last Easter: the only thing Stavroula would serve was lamb—roaste

d on a spit in full view of the diners—with Smyrna figs and htipiti, a feta spread garnished with red pepper. Fixed menu, no alterations, no starchy sides. One long table that seated everyone. Strangers sharing the holiest meal, eating with their hands or they could go someplace else. And he saw how well that went, so. She got her way because she did not give up, and because she fought only for what was absolutely necessary for survival and good food, which were the same thing. She had only ever lost once, and that time it was July who had said no, and Stavroula took it. No fish heads in the psarosoupa, July, no problem. But Stavroula would win today. Love would.

For over a year, she had been in love with July. Had done nothing about it, the only thing in her life she didn’t seize. Until now. She felt for the printed email in her pocket. It was strange that in this moment of exposure—probable judgment—the email from her father would come as a comfort. The ice machine trickled, gurgled, which she felt at the back of her own throat. Not that she’d show it.

Mr. Asbury said in his soft, courting voice, “Even this one?”

“July.”

“The spicy pork tacos?”

“July.”

“Crab cakes?”

“Late July.”

July Angel Hair served alongside Tarragon Lime Bay Scallops. Roasted July Poblanos with Cashew Chipotle Sauce. Classic Chicken Salad with Red Grapes and Smoked Almonds: For July. July galette. That one she would layer with leeks, zucchini, and green chilis, topped with a creamy, tangy avgolemono sauce. It’s not just that she added July to all of the names of the dishes: that would have meant nothing. July was the inspiration for every flavor combination. If everything’s July, Mr. Asbury might say, then what’s July? But then, he did not understand the full complexity that was July. For that matter, neither did Stavroula. For that matter neither did the ex, Mike, who, until six months ago, had ordered items not listed on the menu and barged into Stavroula’s kitchen and used his fingers around her plates. These days, Mike was just a customer. He ordered off the menu and didn’t come into the back. That was the first indication that July was done with him. Maybe all men.

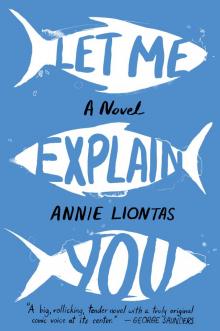

Let Me Explain You

Let Me Explain You