- Home

- Annie Liontas

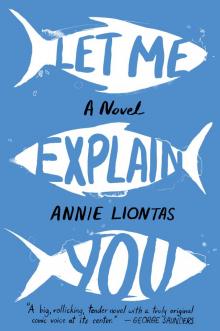

Let Me Explain You

Let Me Explain You Read online

Thank you for downloading this Scribner eBook.

* * *

Join our mailing list and get updates on new releases, deals, bonus content and other great books from Scribner and Simon & Schuster.

CLICK HERE TO SIGN UP

or visit us online to sign up at

eBookNews.SimonandSchuster.com

for Sara, my favorite

PART I

DAY 10

* * *

Acceptance

Let Me Explain You Something. We start from the same sea.

This, We shall repeat.

CHAPTER 1

* * *

From: [email protected]

To: [email protected]; [email protected];

[email protected]; [email protected]

Subject: Our Father, Who is Dying in Ten Days

Dear, Family. Daughters & Ex-Wife:

Let me explain you something: I am sick in a way that no doctor would have much understanding. I am sick in a way of the soul that, yes, God will take me. No, I am not a suicide. I am Deeper than that, I am talking More than that.

DEAR STAVROULA, MY OLDEST. Please grow out your hair. It is very very short. This is one little thing that can change everything, you will see what I am saying when you take this small but substantial advice. Sometimes if we are who we are supposed to be on the outside, we are who we are supposed to be on the inside. The hair is the thing to trust and leave alone, and it will take care of you.

Let me explain you something: your father has seen some of the world for it to be enough. There is a way to be for the normal society, and you are not it. The hair says things about you that, yes, they are true, but the hair is not a fortune-teller. The hair is not the thing that has to point the way, like a streetlight.

I am not somebody religious, but this I know: Death is coming. In ten days, I promise you, your father the man will cease, he will be dust, he will be food in the worms. What do we owe our father? This is the question you can say to yourself at this time. Who can deny a dead man—a dead father—the thing that he demands?

No, I am not sick like my brother in Crete, who die with emphysema (this is Greek en which means in and physan means breath).

DEAR LITZA, MY SECOND, please go to church. You could say, no dad, you go to church then we will talk about if I go to church, but what I am talking about here are lessons that I should have taken for myself if my father had the wisdom to give me awareness, which I am holding out for you.

Litza, let me explain you something. Litza, you have problems.

Litza, nobody marries for a big wedding and then divorce one week later. When your mother and I divorce, it took years off our life. Litza, nobody destroys property the way when you come here into my diner and smash the dessert case with my own stool. The same is true for your sister, which you take that same stool and break her car window with it, even though you deny this always. Are you on drugs, Litza? Are you the same low-life as your biological mother, Dina?

Litza, you need God in your life.

Litza I see how much helping you are needing, and I know that God has to exist, because he is the only one who can do for you. I cannot do for you. I can only do for you what I am done for you.

And here, I will tell you this secret, that I have questions for God—Are you real? Are you here for me, Stavros Stavros Steve Mavrakis? Am I Your Forgotten Son? What is the meaning of this life that is too sorry for what it could be? Even though I have succeeded more, much more, than any foreigner would do in my country and I have now two diners and plans for selling one of them so that I have a little something for the future, yours not mine since my future is not something I can belong to any longer, and not your Mother since she is a thief, I’m sorry if it is a truth.

I, Stavros Stavros, have ask God to erase the mistakes of my life; and God has answer, in a matter of speaking, That it is best to Start Over, which requires foremost that We End All that is Stavros Stavros. No, not with suicide. With Mercy.

Yes, Litza, you must go to Church. To pray. For your father, yes, and for yourself.

DEAR RUBY, MY LITTLE ONE that I have adoration. It is a good rule to follow that if the mustache is weak, so will be the man. Look at your father’s mustache, which it is a fist! Forget the boys, Ruby, find yourself a man who encourages you get your own education, because you don’t want to be one of those woman who takes and takes and does not appreciate all of the way her husband slaves, like your Mother. Don’t go marrying some losers. Which you know I am talking about Dave. Why choose a man with the facial hair of an onion? When you can choose instead one of my assistant cooks, who make a decent living and has dreams of owning their own diner the way their mentor has, which is your father.

Otherwise, you are doing OK.

DEAREST MY EX-WIFE, Carol, the Mother, who divorce me one year ago. Which I am still, as a generous person, paying for things like to repair the plumbing. I am talking to the woman who is still my Wife in death, even if she did not know how to mourn me in life: please be the Ex-wife a Wife should be, in sickness and health. Even though you poison Stavroula and Litza against me from the moment I bring them into this fat country, and Ruby from the moment you bring her into the world. That is why I am asking: you should wear only black for the next year. To show a sign of honor for the man who walk much of this life with you by his side.

If you have any confusions, Daughters and Wife, you can email a response. I will answer them all. Such as, what is missing for a man at the end of his life when the path is clear and wisdom is the greatest? . . . the respect and love for the pateras!

Signed within Ten Days of Life Left, and a Dying Promise, Your Father: Stavros Stavros Steve Mavrakis

DAY 9

* * *

Denial

CHAPTER 2

* * *

Stavros drove away from that Club of Cunts, that Whore House Starbucks where he Fucked Her Virgin Mother. Fuck the Cunt That Threw Her Into This World and ruined his life. His Ex-wife, the Horn Fucker, the Dick-Dinner Eater, who only cared about servicing One Faggot After Another with Cappuccino, rather than care about him. The Fucking Mother, he was finish with her. She could Go to the Crows in Hell with her Divorce and sit there without sex.

He said, “God, if you listen to anything a man say, let her die alone.”

He heard himself talking and the words sounded ugly, like bits of fat, which was how he had intended them to come out. He said again, “Alone, do you hear me?” He wished the Ex-wife, the Mother, were here so he could say it to her face. And then, because God was not really paying attention and could not judge him, Stavros Stavros began to cry.

He did not really want his ex-wife to die alone. What had happened was:

Carol refused the flowers. Yellow, with bright red centers, as if they were trying to convince people they had a heartbeat. He chose them for that reason. He bought them for her. In their marriage, Carol had complained about flowers, Where are the flowers? when he would bring home bouquets of leftover pot roast. She was too simple; a roast was worth more, much more, than flowers; he had gone a year, sometimes, without roast. In their marriage, she looked at him strangely when he said, Why would I love you as much as flowers when I can love you as much as meat? And here he was, bringing flowers to her Starbucks drive-through, being a romantic and a gentleman and a truce, and for the third time she is refusing taking them!

He only wanted to end things the right way, the proper way. None of them do things right. Litza, she is angry and uses her fists to strike empty air, when by age twenty-nine you should move on with life (didn’t he?). Stavroula—thirty-one—she is busy, always busy so she doesn’t have to be anything else. They all

live on Facebook, as if Facebook is Facelife. His little Ruby (twenty-four? twenty-three?), she can’t even call back. But Carol gives him coffee. He does not even have to tell her triple macchiato with three packets of sugar; without asking, Carol knows. That touched him. That made him sure that she had to be the one by his side when he was taken. There had to be someone. He might be ready, he might know to expect death in nine days, but that did not mean any man should face his conclusion by himself in a place like crowded New Jersey, America.

Being alone in the last days of life was like being the last star in a galaxy, watching one neighbor star after another blink into nothing, until even the faraway, nub stars are just light-years, just messages from a dead source, and all Stavros is left with is debris from the first cough of creation. And does Stavros look like a cough? No.

A long line of cars was trying to get his attention, but he did not care. He could be Jersey driver, too. He could be spoiled Starbucks exactly like his ex-wife. Out of spite he would let the coffee get cold and the stale pastry more stale. He could stay until six o’clock if he had to, if she made him, because the only thing needing his attention today was dinner for the goat. He could get one of many tools out of his trunk and open one, two tires of the beeping cars behind him, and then the customers would be spoiled like him, in no rush to go anywhere. He could do that, he had very little to lose. Except time—he had far less than she did, actually, and far less than the rest of the drivers making noise behind him, he had nine days left, which made him terminal—so maybe, no, he was not prepared to wait until six. Actually, he was ready now for her to come with him.

He said, “We know each other, twenty-five years. Twenty-five, you don’t close your eyes on that.”

He noticed for the first time in twenty-five years that her eyes had lightened from the wet-barrel brown of the first day they met to the speckled brown of cork. Her hair, which she highlighted with streaks of red, denied all traces of winter, all gray, which he knew to be her natural color whether she wanted to admit that or not. She had put on weight since the last time they talked. She was full in the arms and face, like a sow holding more milk than her share. Her nails were painted peach, which meant they were painted almost the color of nothing. Her face was puffy at the bottom, but it was bright through all the lines. Like happy, to spite him.

Stavros tried to explain: no man’s days were as questionable as his final ones. The days of a man’s youth were half days, while the final days were overfull. The very last days told a man, and everyone else, and God, if the days leading up to his last days had been worth living in the first place. Couldn’t she see that? And the point he was making? Never mind the car line for cappuccino. Was she listening? He said, “Come with me today, now, Carol.”

Carol said, “I can’t right now,” and adjusted something on her mic. “You want something else? A pastry?”

“What pastry? Duty, I’m talking about.” Is no woman going to give him what she should? “We are more than coffee. We are twenty-five years of coffee.”

When they first met, he drank only instant—Nescafé, crystals that looked and tasted more like dirt than beverage. Carol made pot after pot of home brew, but he never drank it, and eventually she switched to instant, too. It was better that way. For them both, she whipped the Nescafé and sugar into a froth, and for years this was the only way he drank it. Then she got a job at Starbucks and switched to French press. He got a black mistress and switched to espresso. She divorced him, and he snuck back into the house to steal from her own kitchen the Greek cookbook he had given her on a birthday, because what was the need now for any Greek in her life?

Carol said, “I could get off a little early if you want to have dinner.”

He tried again to make her understand what he was actually wanting. It was a very simple, pure thing, which he was confident he could make her realize. All I am asking, he tried again, is that you come with me to some few places now. You are always good at shopping; you are like expert at shopping; you are so good, you almost ruin me, you almost take over my whole life with shopping. No, you misunderstand, I am not meaning to fight with the past, I am only asking that you should make some visits with me today, some few arrangements. Very easy visits. We go to this funeral director. We look over a nice plot, something with a lot of grass. Then we share a meal. Not the diner, forget the diner. We go someplace special at the end.

She was smiling in a way that was compassionate and soft, so he thought he had gotten somewhere. She, the manager, would tell the employees to take care of the store, and she would get into his black used BMW and she would be his witness to these very important arrangements. They would eat together one final time. They would talk about where things went wrong and how, after all, he did work very hard in marriage and business and fatherhood, and she would start to understand things from his perspective, which was of a man with some certain troubles. Then he would drop her off at her white used Lexus, which he had bought for her, and they would end, if not as friends, as co-workers in a labor of life. But the soft smile was not for Stavros Stavros. She was talking into the headset and making apologies for him having car trouble. She was saying to the customers that Starbucks would have baristas come directly to car windows, if the customers could only be patient a few moments longer, and she was offering complimentaries to the angriest ones.

This is what a woman, his ex-wife, was like. He could see that to gain anything, he would need to get angry.

He cast the yellow flowers into the backseat, which he had been holding this whole time as if they were proof of his very good intentions. He said, “You want to come or no?”

She continued to talk, not to him. Always talk-talk, not to him. That was what was to blame for their marriage failings, not his mistress. For months, he had had to hear how he was not the man she wanted, that he would have to figure out exactly what she wanted and then become him. But to be that man, he would have had to become Starbucks. She was in love with Starbucks. Starbucks became more important than making him dinner or washing his clothes or having coffee together or going on cruises or listening to the problems of the diner or the daughters; it became a way for her to reinvent herself, which he did not see the point of. It gave her new friends, which he never trusted. It gave her purpose that had nothing at all to do with her children or Stavros. It gave her hope, which he did not understand or believe to be necessary in her case; it accused him as the reason for her hopelessness. He knew, before she had left him, that she would; he had seen the future of their divorce, just as he had seen the future truth that she would make top manager. Now, because of a dream and a goat, he saw the future again, one where he was dead and she making bigger and bigger boss, with all the hard work of their years together wasted!

He said, “You want pay? I pay you. That is nothing new to me.” Then, “Or you.”

Talk-talk.

Carol of twenty-five years ago would not recognize herself taking orders from strangers in this headset and man’s black-collared shirt. She had stopped carrying her body for others and carried it now only for herself. This was admirable, in a way, but selfish, too, and hurtful, because for a long time she had dressed and carried herself as his wife. He put the car in drive and stared ahead. “It’s always money with you.” This made her push the headset away from her mouth. She started to talk, this time to answer him, but he interrupted. “I am talking about a dying wish, I am asking only a few hours, but you are only, as usual, for yourself. As usual, you are a thief of a man’s life.”

Carol shut her mouth. She changed what she was going to say. “Whatever you’re planning, Steve, don’t bother. I don’t feel sorry for you.”

“You don’t believe me because you don’t understand. But we don’t choose when we go, we just go.”

She went talk-talk about how she was trying to be friendly, she would have gotten food with him (food he would have to pay for!) but, as usual, he was only thinking about himself. She was moving her sow body away from

him even as she spoke, her hands attentive to the drinks. She stirred someone else’s coffee with more love than he had ever seen her stir his. She said, “Venti no-whip mocha.”

“You want me to leave, good luck. Now I will just sit here and take as much time from you as you took from me my whole life.”

Carol shoved something metallic and heavy, he could not see what. Her mouth was twisting, a sign of danger: you did not mess with her soul mate, Starbucks. He felt nervous, like he was about to receive a punishment he did not deserve, even though his anger was a reasonable thing: he would end up with a lap of something hot. He prepared to be scalded, even as he knew she was not that kind of woman. It took a man to punch holes into walls.

“You have final requests, Steve? Take them to your black bitch.”

“Yes, that is where I will go, exactly as you say, and you can go straight to your black-coffee-bitch Starbucks.”

Then he was leaving, he was gone from that Venti Mocha Whipcream White Whore. He was like all those other Jersey nothing-no ones, trying to beat the traffic to the one place that would make him feel like a person that mattered, and that was far from his ex-wife the nothing-nobody Dick Hunter. Stavros parked his car. He adjusted his shirt, which had wrinkled out of anger. He used his palm to calm his hair and mouth. He reached into the back for flowers, still bright, only a petal or two damaged.

Stavros could hear Rhonda typing before he saw her. From the door, even sitting behind her desk, he could see how much space she took up. She was a big black lady. Her arms were the size of his thighs. Always, she had her hair arranged into shapes that told people—told him, the first time they met—that she was not weak. Her hair obeyed her, her hair was solid object. It made him want to touch it, and when he finally got to, it was all he could keep his hands on. Ela, except for her big breasts.

Let Me Explain You

Let Me Explain You