- Home

- Annie Liontas

Let Me Explain You Page 4

Let Me Explain You Read online

Page 4

That’s when Litza saw Toast Delight. Surrounded by self-respecting dishes was the concoction of warm milk and cereal and chocolate, the only meal she had ever actually seen her father prepare at home. It stunned her to see something so private listed at $7.50 and “New!” As children, Toast Delight excited and disgusted them. They forced their way into the kitchen, led by Mother, to gawk as their father poured milk into a bowl of frosted flakes smothered in Hershey’s syrup and chocolate chips and graham crackers, topped with refined sugar, and then boiled it in the microwave for a good two minutes. It was more porridge than toast, but porridge to him was white and tasteless. Toast Delight, he called it, because if I say cereal, you think cold. Toast, they all called it. They squealed. Did he wink at her, at them, every time the buzzer went off?

Litza did not want to admit it, but she had always wanted to try it. She was pretty sure that Stavroula had wanted to try it, too. Dear Dad: How about some Toast Delight?

It was Marina, not her father, who appeared at the table with a pot of coffee. She stuffed herself into the booth. Without saying hello, she poured coffee and dribbled creamer into Litza’s mug. It was the generic, pale drip that no one in Litza’s family drank but Litza. Even Marina liked Greek sludge, so this “American spit” coffee, as Marina referred to it, was something of a peace offering. Marina saying, No hard feelings, because this was the first she was seeing Litza since the post–wedding cake display. Marina saying, It’s OK you come into my house and break my things. It’s OK you keep the wedding gift even though you end your marriage one week later. Like all Greeks, Marina loved being in a benevolent position to forgive: it got her off. In the card, Marina had written To a new life and included a check for two hundred dollars. It was a significant gift, one that suggested that maybe Marina actually cared about Litza, but that possibility disappeared as fast as the money when Litza cashed the check.

“Your father, Litza, he is sick?” Marina was stirring the coffee like that might make it stronger.

“You would know, you see him every day,” Litza said. “I haven’t seen him in a year.”

With two fingers, Marina summoned a waitress. “The big baby, whining about life again. Let’s give a little more work for him to whine over. Two egg plates with home fries. Scramble for this one. For me, fry the eggs until the yolk is dead. If they are wet at all, they go right back. Tell him not to screw it up.”

Though she had known Marina all her life, it was the first time Litza had ever seen her talk to a waitress. “You’re such a bitch when you order.” The first smile.

Marina winked. “You can fix anything in the kitchen unless it’s burned or unless it’s eggs. Or unless it is your father with his crazy ideas.”

Litza felt a prickle with father. What were Marina’s intentions?

Not for the first time, Litza wished that around everyone’s neck was a name tag, and this name tag was in a plastic sleeve to protect it from dirt and spills; and typed beneath the person’s name should be a diagnostic code—such as those from the International Classification of Diseases (ICD–9), to which she had to refer every day and so knew intimately and irrevocably—and that these codes defined what a person needs and what they’re hiding so they aren’t forced to say and you aren’t expected to decipher. In a crisis, they’re just given what they need and you’re immediately clued into what the hell is going on.

Marina’s name tag would read 401.9 for Hypertension with a few postscripts like Prying Dramatic Hysterical Old Greek Woman and Stubborn Racist Spinster. And Self-Righteous Judge. That, she shared with Stavroula.

Litza said, “Did he send you to deal with me?”

“I send me.” Marina’s big arms, folded across her bigger chest.

“You saw the email.”

“Of course.”

“You get one, too?”

“No, no letter for Marina. Add Marina, and the email goes on and on forever. Your father has too many women to keep track of as it is. Marina is just the hired help.”

Marina was not just the hired help. Marina was pretending to have no loyalty to Stavros, and everyone—Stavroula, even—could believe it, but never Litza. Marina had her hand in every pot. They both knew why Litza was here. He had called for her, he was going to recite all the problems listed in the letter, all the things wrong with her, and part of her wanted to sit here until he said them to her face, and that same part of her wanted to sit longer, beyond that. Marina was priming her. Marina was sent out to see if she’d break any more dessert cases.

“What is it you want to say to me, Marina?”

Marina took a long sip of the shit coffee. “Is your father right about Stavroula?”

“You read the letter.”

Marina waved her hands dramatically, making the air around them talk along with her. “Everybody has to forget the letter, Stavroula especially. You, especially.”

“Why?”

“Because it is wrong.” Her stewy eyes flicked once, twice over Litza. “Isn’t it?”

Before Litza had a chance to respond, they both saw Stavros making his way through the restaurant, eyeing Marina and Litza as if he did not want them to leave before he reached them. He was waving down Kelly the waitress. He was touching a young customer on the cheek and checking to see that Litza caught this. Litza and Marina could have gone back to talking, but they watched him. Until Marina said, “Your father is the kind of man who needs to be cut with cream. Women like you and me, we know exactly how to cut him. You make him forget this dying business, Litza.”

At Marina’s insistence, Stavros sat down and took over her cup. The waitress came and dropped the plates, and he took over her breakfast, too. He rubbed his knee. He watched Marina head back to the kitchen. Then he turned to Litza. “Want some milk? To drink?”

Litza almost said yes. This close, she saw how bottom-heavy his face had become. His jaw looked like a fossil. Where was the rage of the 301.3 Explosive Personality she recalled so vividly? Where was the 301.3 that had been threatening them all their lives?

“You like the dessert case? Better than the first, even. We call her my Show Off case.”

“You never replaced the stool.” It had a rip in it. Litza recognized its lightning pattern.

He turned to see the stool, the fat man perched on it, said, “We keep it for memories.”

She followed his eyes, which she knew to be as alert as bear traps. She realized his question about milk had been genuine. He writes a letter about her barren life, and then asks if she wants milk? What does he want her to do with milk, when he’s never once, in living memory, given her any? The amount of milk he’s never offered her, she could spoil in it.

“How is work?”

“I quit.”

“Quit? What kind of quit?”

“The kind where you leave and never come back.”

“You mean fired?”

“No. Quit.”

He grunted. He busied his mouth, then tapped his fork at the edge of her plate. “That is not true. You would have order something bigger if you have no money for food. Somethings To Go.” He knew her quitting was a bluff. He smiled to say, Let me in on the joke.

They were eating together. They hadn’t done that since the night of the wedding, after which they danced father-daughter, after which he loaded the extra alcohol into the back of the car and kissed her on the cheek. The morning of the wedding, he made her cry over money. But that was not why she smashed his original Show Off dessert case.

“I can see that you have trouble with my email.”

She watched him wipe his mouth three times. Finally, he was here. Finally, so was the Xanax. It spread over her lap like a warm napkin. She said, “No, not really.”

“OK, but your face, it says to me you have difficulty knowing what I say. It takes a long time to put my thoughts together, so it is good you come see me in person.” He ate some more, nodded. “There is too much of one life to fit in one letter, is why.”

“What did you ca

ll me for?”

Stavros paused. His forearms were propped against the table, his fists loosely curled. He opened his mouth, closed it. He said, “To have lunch with your father.”

He said lunch as if it were a weekly occasion, as if they had done this when she were a little girl when in reality he did everything he could not to be around her. He casually mentioned lunch. He put together lunch and father as if they weren’t the banging of pots and pans that frightened away strays. Even through the haze that sat on her tongue like a pad of melting butter, Litza felt the anger, the nostalgia for evil words he used to spout. His death, it should have been her idea. But even this she felt at a distance, because of the Xanax. She stared at his sagging clavicle. How was he so weak all of a sudden? She put down her fork.

“Why did you call me and not Stavroula?”

“Your sister, she will come around. But you”—he used his fork to gesture—“I think you take a little more consoling.” By consoling, he meant cajoling.

Litza said, “What else could you possibly have to say to me?”

“Nothing about the past, only the future.” He said, “After we finish here, I have an oraio book for you in the back. Which it is called”—he closed his eyes for the title—“To Live Until We Say Good-bye.”

She laughed. Dear Dad: You are ridiculous.

He frowned, the first one for her today, which was satisfying. She thought about telling him that the only lesson he had ever taught her, anyway, was that Living was Goodbye, but she was caring less and less. He was getting more perturbed than she was.

“OK,” he said, “there is one thing you can do for me.” He pulled a magazine from his pocket. It was turned to the Premier Coffin Selection page. The coffin he pointed to was very distinguished mahogany. “They have coffins made of cardboard, even leaves. They try to sell me one of banana leaf for biodegradable.” He chuckled again. “I tell them only the best for Stavros Stavros Mavrakis. Something solid, strong. Who cares about environment at a time of a man’s death? They don’t understand. My English is not so good for this strange type of thing. You can call them for me, give my order.”

He was full of shit, her father. He was not dying. She could not imagine him in a coffin. He would be staring at her the way he was now, waiting for her to acquiesce. She tried to imagine him cremated, but all she got was cigarette ash, and that wasn’t right, either. That was too much a daily part of her life.

“Do they know you’re making it all up?”

He frowned again. “Listen, Litza, your father, he is not anything if he is a joke.”

He got up, crossed to her side of the booth. She was slow to interpret what was happening, did not recognize what he was doing until it was too late, and she was penned in. She had never known him to sit next to her unless they were at the counter and he was ignoring her to talk to customers and associates. Like this, they were as close as they had been for the father-daughter dance, only not touching, and not for other people watching. She did not like seeing the saggy, wrinkled skin of his arms, the way the watch loosened his wrist.

Dear Dad: Don’t sit so close.

She used to think about hurting him. She used to revel in what it would be like to put lit cigarettes very close to his eyes, because she thought that he would have done the same to her if it weren’t for the two or three obstacles in his way. She had wished his death many times.

She said, “I have to get to work.” Coming was a mistake.

“Now listen to me. This is important.”

She was embarrassed and alarmed at the tears in his eyes. She saw him look away first. Dear Dad: Too late.

Who was this wrinkled, almost gentle person? What had happened to the man who was more volcano than father? Had he gone dormant, reduced to a slumbering mound? Had the dangerous lava become nothing but rock and, at worst, souvenir? Were there flowers and sparrows nesting somewhere on his old, sensitive skin? Was this why he wanted a funeral? Because he wanted one last chance at Vesuvius, and otherwise he was some quaint Greek village mountain?

“We can choose these things together,” he said. He reached out to put a hand on hers.

She said, “Let me out.” She felt a tear in the shape of lightning run through her. She was sure she was going to scream, and go for the stool with the scar, and push off the fat man, and ram its metal legs through the angelic bakery case.

He saw this. He shifted across the booth’s fake leather bench in fits. She waited until he was standing before she pulled herself up.

He said, quietly, “You want to go to the back? I help you, you help me a little?” He was rubbing the air with his thumb as if imagining that it was the back of her arm, just above the elbow; or he was actually rubbing her arm and to her it felt like nothing.

Dear Dad. “You want to know what they should bury you in? A hole.”

She left him to finish his eggs. She buttoned her jacket and kept buttoning even after it was clasped.

The odor of incense does not tell you what, it tells you when. It speaks to the time when smell will be all that’s left of you.

CHAPTER 5

* * *

Ever since his vision of death, the smell of incense has been on him. It comes at the moments Stavros Stavros Mavrakis least expects it, and then disappears with no explanation.

The Goat of Death was what brought the bad news that death would come. The goat appeared first to Stavros in a dream, which he considered a nightmare, and then the next day it showed up at his diner, even more of a nightmare.

He was in bed, cold, with no woman but plenty of woman troubles, and he was dreaming of home. His Crete, his island, which he had not seen in some months, which missed him as much as he missed it, which was going through a very tough time economically without people like him. At the top of a gray peak was a white church that, from his place at the base of the mountain, looked like a rib poking out of the earth. Next to the church was a white goat exactly the same size as the church. He blinked once and then, because he was dreaming, Stavros was next to the goat and the church; actually, he was beneath the goat and having to stare up at its dirty chin. The goat smelled like dirt and incense. The goat looked out with eyes as lifeless as one-dollar bills and the same green. There were no shepherds on the goat’s mountain. There were not even bodies in the graves behind the church.

The goat pounded the hard dirt with its hooves. It was very strange and scraping, a shovel noise. The smell of incense got stronger, and a smoky cloud appeared above the goat’s head. All around him, Stavros felt a Stavros-shaped hole being made by the hooves, as well as a God-shaped one because God was not here for him. And while he didn’t feel anything of the hooves on his face where they struck, he did feel himself being pushed and buried. The earth opened. His own last breath was coming to him. It sounded like a gurgle, a sound too tiny for his whole life.

Stavros went down shouting, Wait, Death! You must give me more time!

The goat listened, the incense hung in the air. The goat struck the ground ten times. It was hard, like stone on metal, blacksmith’s work. Ten times, ten days. This was what he was being given.

In the morning, Stavros woke up and said to the nobody sharing his bed, “That is one crazy dream I would not even want my mother to know about.” He took care of regular business—bills, phone calls, sitting with the old man who came only for soup six days a week. But all day he was unable to help himself, looking at calendars and at his reflection in the display case, adding up all the hours left between now and—he snorted—ten days from now. But the day wore on, and mostly he forgot. Then Marina, when he was reading today’s paper, undid him. Marina, the one person he could never fire, the person who could almost fire him, said, “There is a goat here for you, Stavro.”

“Who goat?” He stood. “Don’t say the word goat.”

The Goat of Death was back, on his property. The goat was early!

“You want me to take care of it for you? A nice goat stew?”

No, no,

no, he had to take care of it. Stavros said, “Give me the biggest knife you have.”

“You, who is afraid of meat when it’s frozen. You have to earn a knife like that, Stavro. Get yourself a little trap from the trap store, or better to let Marina handle it.”

He was not afraid of meat, frozen or not: he was as much cook as she, almost. But he was afraid of this goat. He could not let anybody know that. “I bring you a new special tonight, goat all ways.”

“Goat no ways,” she answered back.

She shuffled off from him, insolent. She gave him that slanted bun on top of her head, the wet rag on her arm, the big white exclamation points of her calves in their black work sneakers, which were somehow like slippers. That big fat Greek-woman ass in its gray skirt, like if it was meat product.

On the wide top step in front of the diner’s glass doors, Stavros and the goat faced off, only the goat was not facing off, only scavenging. Stavros knew immediately and was calmed: this goat was not his goat. It did have a dirty white chin, but it was black with black ears and a flicking tail. Young, thin, only its horns full grown. A common goat. It did not smell like incense. It smelled like poor men. Strangers were coming in and out, watching to see what Stavros would do, and these strangers would tell their friends and their friends would tell his enemies, some of whom were his friends, and he would lose business and the face of his reputation. So he joked, “Free goat for every happy customer.” But he had no joking feeling inside. This was not Welcome-Welcome Stavros with a sweet pear in his pocket for children, even the teens who walked in at eleven thirty and only asked for one fries to share for five people. This was a Greek man with a strong business mustache and ten days promised to him and he was not going to be beat or embarrassed or made fool by just any common livestock. Stavros was not going to be Mr. Nice Diner anymore.

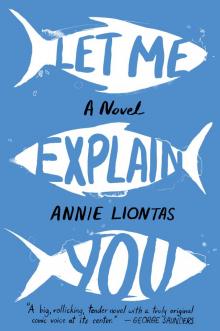

Let Me Explain You

Let Me Explain You