- Home

- Annie Liontas

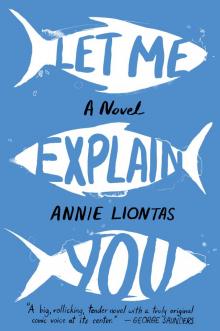

Let Me Explain You Page 6

Let Me Explain You Read online

Page 6

Stavroula said, “Are you going to tell him you’re married now?”

“Who?”

“Dad.”

“I’m not gonna keep it from him.”

There it was, the thing that separated them: if it had been Stavroula, she would have gone along in secret. If the elopement had been a chicken, Stavroula would have plucked its feathers and boiled it down to dumpling. No, Stavroula reminded herself: that was before. Post-email Stavroula was wide open. She was writing poetry about a woman and selling it to the public at mealtime. She was eating chicken and smearing her face in the drippings and wearing the bones like a necklace.

Ruby brought a napkin to her mouth. For the first time Stavroula caught the trifle on her sister’s ring finger.

The kitchen was beginning to get hectic, Stavroula could sense it. An order—July’s voice—broke through the atrium. Something sluglike smeared itself against Stavroula’s stomach and left a slimy trail, like a dog tongue on a window or like okra. July was seeing the menu for the first time. Stavroula stood and asked one of the boys to get Ruby a frappe to go. She put her hands on her waist to give the impression that she was composed but obligated. “Sounds like I’m needed.”

A nod, then Ruby took up her jeweled phone. She said, “Catch you at the wake.”

Marina had taught her: in the kitchen, there are three kinds of proxemics. Intimate = six to eighteen inches. The people who cook with you, or the people you cook for, they fall within this reach. Often, you’re coming into actual physical contact. Sometimes the closeness is too much, and this is when dropping your eyes helps. Stavroula, of course, having been trained by Marina, was not one to drop hers. Social = four to twelve feet—her kitchen vs. the dining room, her staff vs. the waitstaff—the distance at which most precise work takes place over a fourteen-hour shift. At once estranged and familiar, Marina explained, social distance creates the phenomenon that a good waiter senses, without being told, what the kitchen is short on and makes a perfect alternate recommendation. Like a lover loping gracefully despite the darkness. Despite it, koukla. But anything over twelve feet was public distance. Supreme formality, plus enough space to escape in case of danger or awkwardness.

And here was plenty of both coming at her. Here was July, a good fifteen feet away, pushing through the prep cooks who knew not to get in the way, staring her down. The dress could have made Stavroula’s menu—fuchsia, ripples at the bottom. Two gold earrings like the knobs of a dresser, the white wedges that Stavroula was fond of and that revealed three, almost four painted toes. Her arms tanner than they should be in April and a little too thin. July held them apart from her body, a gesture both welcoming and repelling. A fence, closed but maybe not locked. Her smile, tailored and difficult to interpret. The smile of a hostess, which she often was. She was holding the menu. Clutching the menu?

And July, moving straight through public space and into social—

For the first two years, they had worked at this distance. How are you, Fine, Enjoy your day off, This your umbrella? This was mostly because July left as soon as her shift was over and kept her office door closed, and Stavroula was not the friendliest. She felt entitled to her temper, just like her father, because she was good at her job. Ask July if she cared about a chef’s petty demands? Or tolerated how controlling Stavroula was? The standoff continued until they both got weary of it, and soon they were the only two women on staff. They started to get a little more personal, but not too personal.

Then came the day they crossed into intimate. A year ago. It was the sun that coaxed them out to the bench on the narrow green behind the restaurant. They peeled oranges. July got up and stretched out on the ground, even though the ground still held the mule cold of early April. She propped herself up with her elbows. She could have stretched out her bare feet onto Stavroula’s lap. She was saying, “I don’t believe you.”

“You should,” Stavroula said. “It’s something I’ve just always been able to do.”

July gestured at Ramos coming up the alley. “What about him?”

Stavroula punctured the orange with her thumb at the thickest part of the rind. One of her claims was that she could remove the skin in a single peel. The other was that she could instantly tell what someone had last eaten by appearance alone. She called out to Ramos, and he said, “Good morning, Chef.”

She said, “You had a muffin for breakfast, didn’t you?”

“Yes, yes, Chef, a muffin.” Ramos’s grin was buttery. “A sweet one.”

“See?” Stavroula said. “Unquestionable gift.”

“Doesn’t count. Come on,” July said. “Try me. What did I last eat?”

Stavroula rubbed her thumb across the skin of her orange and it lifted from the fruit in a single spiral. She shut one eye and looked July over. The morning sun fell around her easily. Her long blond hair was pulled back but a few strands hung around her face, and she was wearing the same emerald earrings as yesterday. As if she had slept in them.

“Nothing. You haven’t had anything today.”

July took the orange from Stavroula, the perfect peel. “That was lucky and cheap.”

“I only say what I see.”

—driving straight through social and into personal space, and now she and July were face-to-face, intimate, with only the heat coming off the ovens to separate them. July’s mouth, a lovely rip, how could Stavroula possibly look anywhere else?

“July Summer Sausage,” July said.

“Yes.” This close, she could have whispered it.

“Pineapple July and Pig.”

“Already one of our best sellers.” BLT with rings of grilled pineapple for tomato, inspired by the ham and pineapple pizza that July had Stavroula make after the kitchen was already broken down. And then she proceeded to eat only the pineapple and pancetta.

“A Whole July Rotisserie.”

“A Whole July.” For the time that Stavroula watched her eat an entire chicken by herself. This one would be accompanied by watercress, yogurt, and lemon.

The joke was fading from July’s face, if it had ever been there in the first place. “July’s July. Really. You put that on there.”

“Of course: a plate of blackberries drizzled with extra-virgin, creamy feta on the side.”

“As Apple Pie—”

“—As July.”

July was keeping her voice down, but just barely. She was not the manager of Salt for nothing. “An entire plate of blackberries? You expect people to order that?”

One look at Ramos told Stavroula that the kitchen staff had been waiting for this: food fed you, but kitchen gossip made you take big bites. It didn’t matter. Stavroula was showing July instead of talking, using her hands, which were becoming a flowery purple by the second, pulling in some pickled red onion, a dash of crushed pepper, large torn leaves of mint. She placed the dish in front of July, added a generous handful of feta with her cupped hands. July’s July. The blackberries were a peal of bells hanging in a church tower, moon unveiling their shoulders. If she didn’t say so herself.

“They won’t be able to help themselves,” Stavroula offered, a little breathless. “We’ll sell hundreds.”

Like that time they—she and July—bungled the produce order and got six times the amount of blackberries they should have. What had happened was, she posted a note for blackberries. One of the other cooks posted a note for blackberries. Mr. Asbury posted a note for blackberries. July posted a note for blackberries. Stavroula approved the order for blackberries when she was “multitasking.” Inexplicably, the producer left them two more crates on top of that. By the time they realized, a return was out of the question. They froze some, they unloaded some to other restaurants, they made ice cream and pie, they delegated to glazes and marinades, they served a complimentary compote to guests, they still had a thousand blackberries left, it seemed.

The look July was giving her now didn’t match the delicacy that was July’s July. Rather, it was like the last day of the berrie

s, when she and July surveyed the damage, the hundreds of blackberries overripened into saccharine mud, the dull and damaged skin, the loose, erupting drupelets. The soft, fine-haired mold that spread like a diseased cloth. That day, it was not exactly disgust that July expressed when she said, “Is it too late for sorbet?” but an exhausted humor that implicated them both. Instead of throwing the berries at each other or pushing one another into the sliding, skating fluids of the fruit, as Stavroula fantasized, they used a mop. They took turns wiping and rinsing, even though they could have had one of the boys take care of it. They talked about their fathers.

“Try it,” Stavroula said. She held out a fork. “You don’t like it, I’ll take it off.”

With her fingers, July took a berry with some onion.

“It’s good, right? Take another.”

July slid the menu across the counter. “Change it, Stevie, the whole thing.” She walked off in the white wedges.

Because the entire kitchen was already part of this, and because Stavroula knew it would expose her as much as she had exposed July, Stavroula called after her, “Next week we add Sorbet in Hot July.” It gave the staff permission to laugh.

Marina had taught Stavroula, this is how you learn who a person is. First, you ask, What was the happiest moment of their life? Then you ask, and you keep asking until you get the real answer, Was it worth it? Stavroula had yet to have her happiest moment: that would come with July, when July was ready.

Wouldn’t it?

Stavroula had slept with a few women. No one she had been serious about. No one worth risking anything for. Everything.

Age five, that’s when she fell in love with the first woman: Mother. Ba-ba’s new wife, who, along with Ba-ba, got them out of Greece, brought them back to America, raised them. As a child, Stavroula knew intrinsically that if you were hungry, you ate what was on your plate—so she had always been grateful to Mother. She adored Mother even now, with everything that had come between them and all the ways Stavroula had been left to fend for herself. If it weren’t for Mother, she’d be married off to some Greek who expected her to clean his fish of the faintest bones. Mother was the first to say—even before Marina—In this country, you can be whatever you want. She had been the one to teach little Stavroula, coming off the couch after an episode of Love Connection, about prenuptial agreements—and little Stavroula responding, “Maybe that is for me.” By which she meant, what women wouldn’t want that?

Another thing: if you were hungry, you paid attention. This is what Mother likes—butter not margarine, television shows where women drift from one room to another, not realizing that some other woman has convinced their men to go away on a trip. This is the way Mother catches the little horse that lives at the end of your hand (your fingers are the legs, the middle one is the head, sniffing around her nightshirt). This is Mother eating burned toast and lukewarm tea, since you haven’t figured out cooking yet. Mother eats as much of it as she can, because Mother loves you. This is what love looks like.

But not at first. At first Stavroula had to earn Mother’s love, just like she would have to earn July’s. Which felt right.

At first Mother said, “If you want to go back, we’ll bring you back.” Because Stavroula, anytime she got into trouble, would cry to go back to Greece. Ba-ba fell for it, but Mother knew that no little girl actually wanted to return to the orange dust, or to the farm roosters that called ruku, ruku at all times of night, or to motherlessness. So, three weeks of these fake Greek tears, and Mother took out a suitcase. The same brown shell that Stavroula had entered the States with. She began to pack Stavroula’s American things. Stavroula, who could not speak English, had to guess at what was happening. She said, “My clothe.” She removed them from the suitcase and pushed them back into her drawer.

Mother watched until all the clothes were in the drawer and then said, “You want to go back, so you keep saying.” She took out the clothes, put them in the suitcase again. “You get what you ask for here. No one’s making you stay. If that’s your home, we’ll send you there.”

Little Stavroula felt a bundle of panic, and it rose to her fists. The first step was the packing; the second and last step was being put on a plane and forgotten. She began to wail, she dug at the clothes in the suitcase. She put them in the drawer, quickly, then blocked it with her whole body. She could do this all day, whatever it took to stay with someone she loved—loved so much it hurt—and who maybe loved her. “Mother,” she said. Not asking: pledging.

“You sure?” Mother said. “You want to stay with Mother? Etho?” Which meant here. One of the few Greek words Mother knew.

Stavroula said, “Here.” She opened the drawer and folded the crumpled clothes the way Mother taught her. She put them back in her drawer. She was not letting herself cry, and this may have been the reason that Mother did not take her into her arms.

“The next time you ask to go back to Greece,” Mother said, “I will bring you there myself.”

Stavroula nodded, grave. “You. I, here.”

Mother did take her, did hug her.

It did not take Stavroula long to figure out what Mother’s happiest moment was. March 2, 1988, 11:08 a.m., the time of Ruby’s birth. And, in all fairness, that would have been Stavroula’s, too, had she been Mother. Stavroula knew that there was something wondrous growing inside of Mother before Mother and Ba-ba told her about it. There was a small swelling on Mother’s stomach that Mother pet and pet, and Stavroula knew that Mother had been waiting for it for a long time. Maybe even as long as Stavroula had been waiting to come home to America, which was most of her life.

Stavroula could tell that whatever was inside of Mother would be more deserving than Stavroula, and it would be worth keeping forever. Stavroula understood that she and Litza were secondhand. They were someone else’s children, dragging around someone else’s problems, while the little girl growing inside of Mother was as miraculous as spit, which is natural to the body. Stavroula felt Mother start to withhold, and she hated it, and yet she knew it was absolutely right. No, she can’t have more new clothes, the baby will need some new clothes. She can’t crawl into Mother’s lap and pretend she is a snail and Mother the shell, because the baby is the snail. The baby is the snail for now, Stevie, OK?

Mother was still pulling Stavroula toward her and calling her Little Yia-yia. It’s just that there was something between them now, something that felt like Mother but something she couldn’t throw her arms all the way around anymore.

She should have hated Ruby. She hated Litza.

For as long as she could, Stavroula kept the growing Ruby from Litza, to protect Litza from knowing, and to protect them all from Litza’s knowing. But when Litza finally realized what was happening, she got excited. Litza was five years old, the baby only weeks away, and she should have long forgotten Greece. But what she said was, “Just wait. After Mother loses all of her leaves, they’ll send us back.”

They were alone in their room, putting away their toys in the bins that Mother had organized. They were speaking their own special Greek—a version that their father would not have understood because it did not exist for anyone else. Stavroula said, “What leaves?”

“On Mother. A big pile of them, in a trash bag under her shirt. You can barely make out it’s her beneath all those leaves.”

“They’re not leaves. They’re little babies.”

“I know what’s under there. I’ve seen it.”

“We’re not going back, Litza. There’s nothing to go back to.”

Litza was not helping to clean. She was sitting on the bed with her knees to her chin, thinking in rough cuts the way only Litza did. Stavroula threw two more dolls into the bin. They were stupid toys—she preferred monsters with strange faces but couldn’t get the adults in her life to accept that. She joined Litza, put a hand on her leg. Litza jerked away.

Stavroula said, “Mother is nice. She’s always been nice to us. Don’t you think?”

“Nice

doesn’t last forever.”

“We just have to work harder.”

“You are such a stupid koukla. Only a foreigner thinks like that.” Something they had heard Mother’s family say about their father.

“At least I’m a good koukla. That’s why Mother loves me and not you.”

“She loves those leaves more than she’s ever loved you.” Litza’s eyes were wet, but not like crying. More like victory. “That’s what mothers do, they have to give up their children for the leaves.”

Stavroula felt a clog in her throat, the same one that appeared when Mother took out the brown shell suitcase. Litza was wrong, she was bad. That was why she couldn’t understand Mother’s love. She had never wanted to. It didn’t matter how much attention or punishment Litza got. Litza didn’t feel Mother’s love like Stavroula did, because Litza didn’t deserve it.

Litza, no longer trying to be mean, said, “Yia-yia was nice, and she was also home. That’s why I’m going back.”

If Litza got them to send her back, they would send Stavroula, too. Litza did not realize everything they would lose. Only Stavroula did. She barely remembered Yia-yia. Yia-yia was the one made of leaves. Greece was what was made of leaves. Stavroula tried something new. “Well that’s why you have to be nicer to Mother. So she agrees to send you back. You have to make a deal.”

“Is that what you did?”

“You make an agreement and you never, ever talk about it.”

Slowly, slowly, it came to Litza. Her body began to rock on the bed as she put the pieces of logic together. She was approaching what Stavroula already knew: If I’m The Way They Want, I Get What I Want. Litza began to rock faster to get to the idea faster.

“You have to be nice to her and to whatever’s inside her, and they’ll let you go back.”

Litza looked up. “You’ll come, too?”

Stavroula nodded. “We go together.”

“You promise?”

Stavroula solemnly nodded. She could promise. She had been taught by adults that a promise was something you said today to make a child do something for you, and tomorrow it was their job to understand why you had to break it.

Let Me Explain You

Let Me Explain You